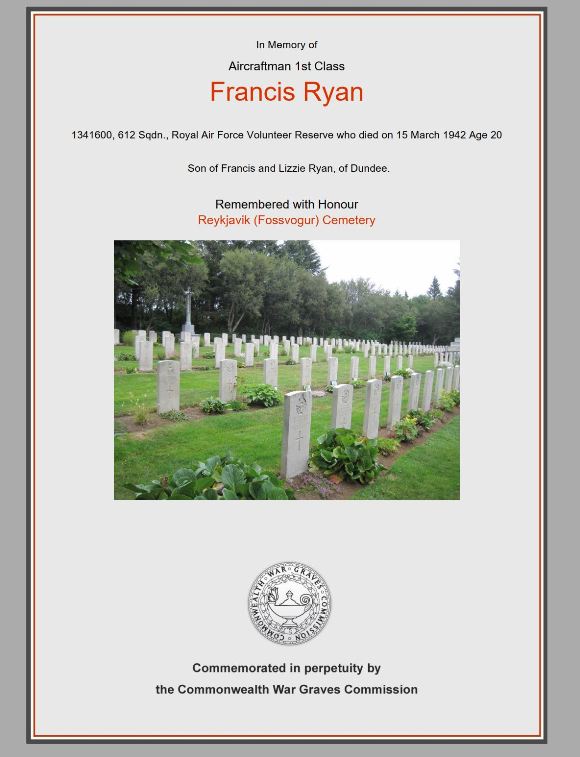

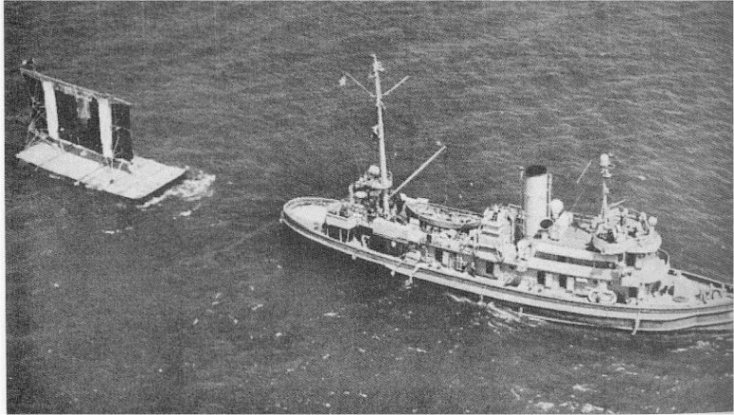

I never knew much about my Uncle Frank’s death, apart from the fact that he’d died in an air crash. His letter to his sister, my mum, that I published two weeks ago, inspired me to search again for more information. This is what I found:

The Incident:

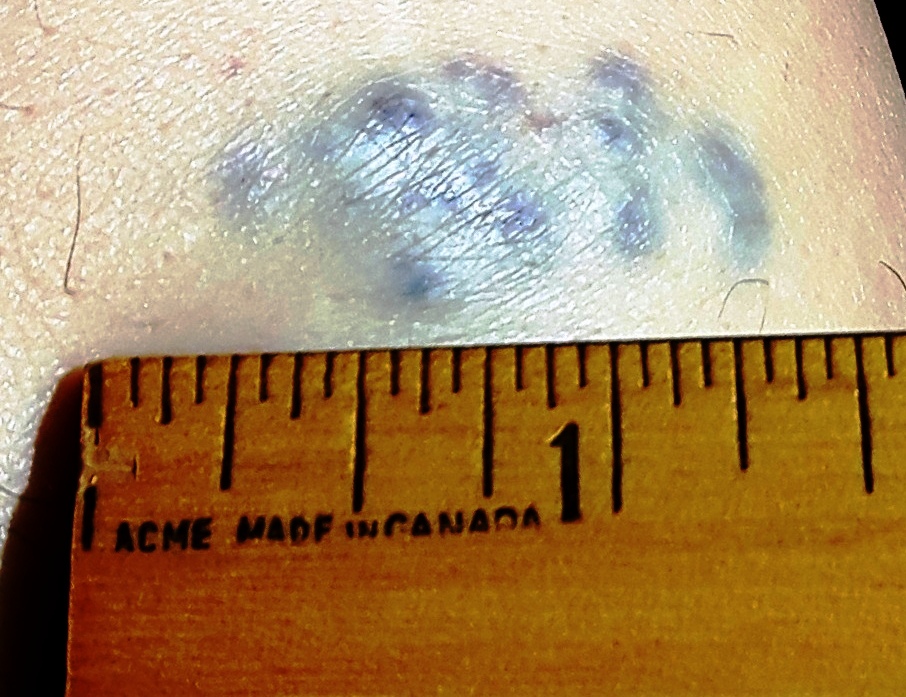

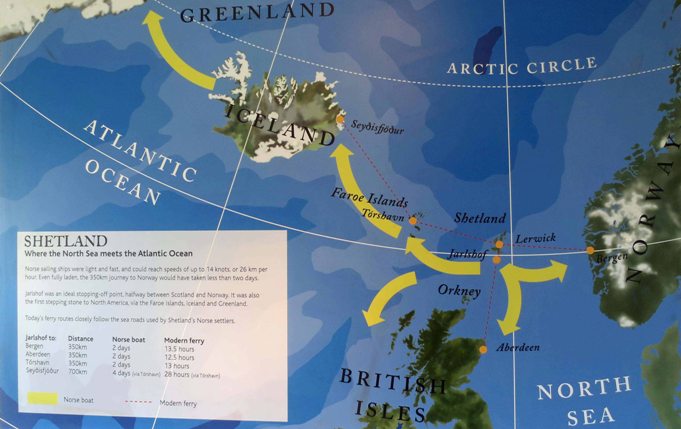

Aircraft WL J took off on a transit flight from RAF Reykjavík at 10:51 hrs, 15 March, 1942. The port engine failed on take off, the aircraft swung off the runway and hit an armory building. The aircraft was destroyed by a huge explosion and fire. All killed in the crash and rest in Fossvogur Cemetery:

P/O C Harrison †

P/O J H Hackett †

F/Sgt J G Turner †

F/Sgt L S Collins †

Sgt G H F Mc Clay †

LAC J W F Allan †

AC1 F Ryan †

(P/O = Pilot Officer; F/Sgt = Flight Sergeant; LA = Leading Aircraftman; AC1 = Aircraftman 1st Class)

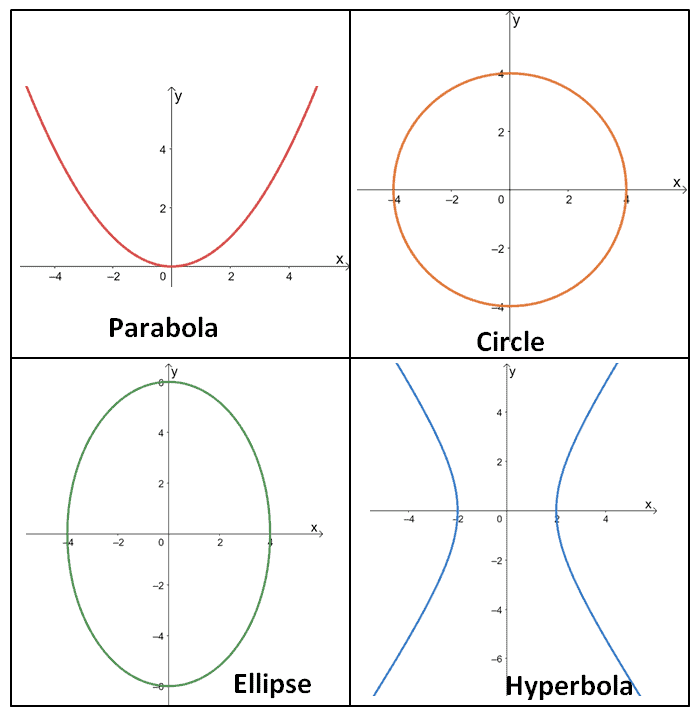

The Aircraft:

Armstrong Whitworth A. W.38, Whitley Mk VII

Aircraft Code: WL J

Serial no: Z6807

Operator: 612 (County of Aberdeen) Squadron RAF

The Squadron was operating in Iceland from 15 Dec. 1941 to 18 August 1942.

Detachment from 12 Sep. 1941 to 3 Oct. 1941.

• Details on aircraft: Wikipedia.

|

|

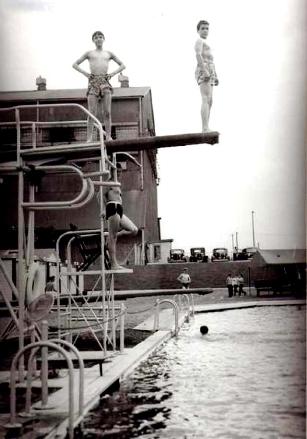

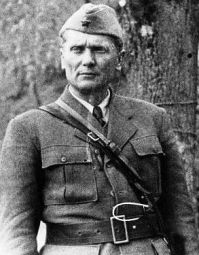

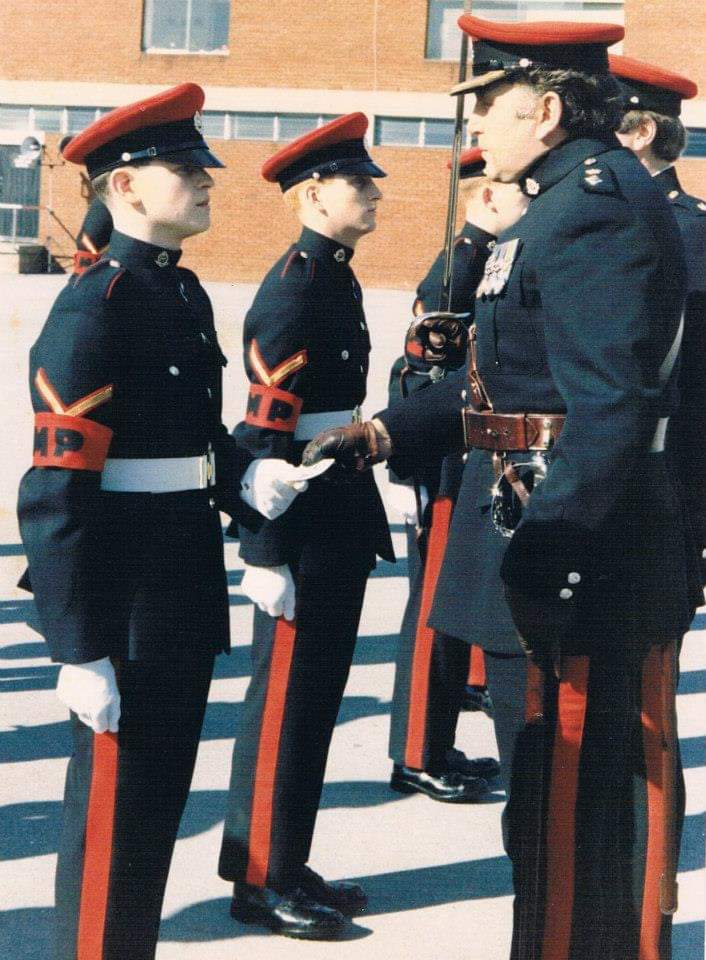

Frankie, nineteen years old

|

|

|

|

The Music and Dance of Scotland.

Brian Macdonald |

|

|

I have a more extensive knowledge of the music and dance culture of Scotland, the third of the three Celtic countries that make up Britain along with England.

My own land has little history of producing great classical or operatic singers. An internet search suggests that the rock-group singer, Annie Lennox, is Scotland’s most famous singer. She still performs, now aged seventy and her repertoire has broadened. She gained international fame with The Eurythmics in the 1980s and is by no means a folk singer.

The Celtic Rock Group, Runrig, originated on the Isle of Skye in 1973 and bade its farewell to an adoring Scottish audience of 52.000 in Stirling in 2018. Some of its numbers are in Gaelic. It can lay claim to being among Scotland’s best-known and most successful musicians. Runrig’s rendition of that most popular of Scottish folk-ballads, ‘Loch Lomond’, was always its closing number and created almost a riot as the audience enthusiastically joined in at every show in which Runrig performed. ‘Loch Lomond’ is thought to date from 1746, the year after the Seventeen Forty-Five Jacobite Rising of Bonnie Prince Charlie and to be the words of a Scottish Highlander, dying at the final battle of Culloden, who will be returning to Scotland in spirit by ‘the low road’ while his love can take ‘the high road’.

Scotland has a tradition of tenors who have specialised in Scottish songs and sopranos who have done likewise. The names of Kenneth McKellar, sometimes called Scotland’s finest singer, and soprano Moira Anderson, who often duetted with him, come to mind from my own era. These two became stars of Scottish TV in the 1950s and 1960s. The BBC, Britain’s publicly owned broadcaster, found it had a major hit on its hands, and not just in Scotland, with ‘The White Heather Club’ which ran from 1958 to 1968 on Scottish TV. The program was devoted to Scottish music, dancing, and comedy, for the Scots have an abiding fondness for their rich heritage of folk music and the tunes of Scottish Country Dancing. This Saturday evening program catered to Scots with a taste for the culture of their own country but had its detractors as presenting a parochial image of Scotland that was not to the country’s best advantage. The first presenter was the operatic singer, Robert Wilson. He was followed by the versatile singer, composer, and entertainer Andy Stewart, who rose to fame with the program and compered it for nine years.

The music for the show was mostly provided by Jimmy (later Sir Jimmy) Shand and his band, already well-known in Scotland for country dance music, when the program began. Shand was an ex-miner from Fife, a grim-faced, unsmiling man who disliked publicity and had no stage presence but was a genius at playing the accordion, an instrument popular in Scotland. Jimmy Shand and his band, with their strict tempo Scottish Country Dance music, were a delight to dance to and he has been called ‘The Victor Silvester’ (Silvester was the doyen of strict-tempo ballroom dance music in London) of Scottish music. Sir Jimmy Shand died aged ninety-two in the year 2000 and his band has been kept alive by his son of the same name.

Andy Stewart was a certain type of Scottish entertainer who flaunted his Scottishness. Born in Glasgow in the west of Scotland and raised in the fishing town of Arbroath on the east coast, he wore the kilt, sang Scottish ballads and comedy songs, and read poems, many his own compositions, and was always robustly ‘Scottish’. He was a prolific songwriter. A Scottish Soldier’ is a stirring song of his which endures and is also often played on Scotland’s national musical instrument, the bagpipes. ‘Campbelltown Loch’ and ‘Donald, Where’s Yer Troosers?’ are comedy songs he composed which also have remained popular in Scotland and ‘Donald’ is known to many outside its own country.

Stewart followed in the footsteps of Will Fyffe and Sir Harry Lauder, both of whom gained international fame. Lauder was reputed at one time to be the highest-paid entertainer in the world and performed in USA, Canada and Australia and headlined Britain’s annual Royal Command Variety Concert. Winston Churchill lauded him as ‘Scotland's greatest ever ambassador’ and the kilted Lauder with his cromach (Scottish long walking stick) was a familiar figure in newspapers and on screen. The White Heather Club’s Hogmanay program, which ushered in each new year at midnight on 1st January, always turned into an exuberant, well-lubricated party, featuring the accomplished comic actor, Duncan Macrae. His rendition of the comic song he wrote, ‘The Wee Cock Sparra’ was always a highlight.

But such uniquely Scottish entertainment is not the sum of Scotland’s musical culture. There is a catalogue of Scottish ballads that lend themselves to group singing, with tunes familiar to and loved by Scots. Many celebrate the land, such as ‘Westering Home’, which celebrates the island of Islay in the Inner Hebrides, famed for the peaty malt whiskies its distilleries produce. ‘The Road to The Isles’ praises the Isle of Skye, also of the Inner Hebrides. Mairi’s Wedding was written to honour the winning of the Mod, a Scottish Gaelic-language music festival comparable to but not as well-known as the Welsh Eisteddfod. Sir Hugh Roberton wrote lyrics to the tune which are enduringly popular.

Not by any means are all folk-ballads from antiquity; some are from poems composed by Scotland’s most-loved and famous poet, Robert Burns, in the 18th century. The well-known Skye Boat Song has lyrics written in Victorian England to an eighteenth-century tune and celebrates the escape of Bonnie Prince Charlie after the defeat at Culloden in 1746 that ended the second Jacobite Rising. The writer and scion of a lighthouse-building family, Robert Louis Stevenson, also wrote lyrics to the tune but they are not well-remembered.

A twentieth century song which has become a loved folk song and been adopted as the official anthem of Scotland’s rugby and football teams is “The Flower of Scotland’. Some think it an awful dirge, but it rouses patriotic sentiment in the breasts of many and is sung with gusto before international games. It was written by Ronnie Williamson, a member of the 1960s popular folk-revival duo, The Corries and celebrates the Scottish defeat of the English by Robert the Bruce (Robert 1st King of Scots) at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. ‘Football Crazy’ was a song written in the 1880s which was reworked as ‘Fitba’ Crazy’ by another sixty’s ballad-singing duo, Robin Hall and Jimmie MacGregor, and became a most unlikely runaway pop hit, but, alas, does not fit the mould as legitimate folk music.

Scotland can boast of its world-renowned Glasgow Orpheus Choir, founded by Hugh Roberton in 1901, at the dawn of the twentieth century and ruled by him for many years. Roberton was later knighted for his services to the arts. Unlike Treorchy, the Orpheus had both female and male members in its near-one hundred-strong band of singers, all of whom had to be of a high standard. Out of respect, the choir was disbanded on Roberton’s death in 1987 but was immediately replaced by the appropriately named Glasgow Phoenix Choir, which, good as it is, has not scaled the heights of fame of its predecessor as choral singing has largely gone out of favour as public entertainment.

But Scotland, while it does not lack singing credentials, leans more towards dance and the toe-tapping music of Scottish Country Dancing. There would never be a dinner dance held in Scotland that did not include at least one Scottish Country Dance. There are many dances, each with its own set of movements and dancing steps, normally danced by a set of four men and four women. There are three types. The reel is a fast, energetic dance, often performed enthusiastically as a ‘warmer-upper’ at events or later in the evening when dancers are more relaxed. There is much spinning of the couples and fast movement in a reel, often with the male dancers raising their arms and letting out loud skirls (shrill scream). The jig is a light-hearted and merry dance with skipping footsteps and the strathspey is a leisurely, graceful dance with gliding steps.

While dance display teams are composed of competent dancers, the men wearing a kilt and a long-sleeved white shirt and their partners in long white dresses with a tartan sash worn diagonally with a silver brooch at the right shoulder and the formality of steps and movements is rigorously maintained, this is not always the case with most dancers. For Scots who love to dance, informality is the rule with enjoyment rather than style and grace the objective. Dress is optional and the steps and movements are less strict. Apart from organised dances, Country Dancing is always a major part of a Scottish wedding or other celebratory party.

Scotland also has a flourishing tradition of Highland Dancing, competitive solo dancing whose birth was in the Scottish Highlands. It features intricate footwork on the toes and precise, formal movements. It has strong links to Scottish culture and history and is very athletic. Highland Dance competition is as much a staple of Highland Games gatherings, with bagpipe music as accompaniment, as are the Highland Sports, heavy field athletics events competed in by brawny men. The dancing is mostly performed by slim young women. The Sword Dance, an ancient dance of war performed on two swords, or a sword and its scabbard laid crosswise on the ground, is a well- known Highland dance. It is said to hail from as early as the 15th century and to be a celebration of victory, performed by both men and women, but frequently now by soldiers from Scottish regiments.

Each country will strongly maintain the reputation of its own music and dance culture, as it should. I hope I may be forgiven for my enthusiasm for Scotland’s treasure.

Just as Wales and Ireland have their harps as their national musical instruments, so does Scotland have the bagpipes. There are those who abhor the sound produced by bagpipes, but there are more who enjoy the stirring music they make. Bagpipe music is used to accompany dancing, stands alone, or is used in military bands, often with the pipe band providing marching music for a phalanx of kilted troops and is best heard in the open air. Other countries have adopted the bagpipes for military use from association with British troops or from a strong connection to Scotland, such as Canada. They are also native to some lands.

I was never a singer. My voice would have embarrassed a frog with a sore throat. I get my pleasure from music by listening to it and dancing to it. With the assistance of hearing aids, I can still listen to my outdated records, tapes, and CDs.

The dancing is ended but the memories linger on.

|

|

|

|

Family Treasure

Hugh McGrory |

|

|

My brother Mike has just returned to Yorkshire after spending a couple of weeks with us in Ontario. As our family archivist he brought a treasure that he had found amongst our Mum’s papers. I want to share it with you.

It’s a letter written by our Uncle Frank to our mother, his sister, while he was on active service in WW 2 . I was surprised at how profoundly it affected me to be holding the same pieces of paper that my uncle had touched and written on more than 80 years ago.

I’m going to let you read it before I add a few thoughts:

I was thrilled to see the letter. It was like a window had opened to let me see what life was like in wartime Scotland when I had just entered primary school (February 1942). For example…

The envelope leaves no doubt that this was wartime, from the “on active service overseas”, to Frank’s Id # 1341600, and the Censor’s stamp.

A brief background… Frank was the baby of the family, and growing up, he had three older sisters -for example, when he was 10, Evelyn was 22, Elsie (our Mum) was 16, and Eleanor was 14. Poor Frank - it must have been like having four mothers to keep him in line! They called him Frankie.

Apparently, I was a chatterbox/gasbag as a four year old – I’m surprised – I thought that I was a shy kid... It seems that Frank and his siblings were on very good terms and were able to correspond regularly - a credit to the logistical capabilities of the British forces – a morale booster, I’m sure.

Frank’s mention of nylon stockings rang a faint bell for me. These went on sale to the general public in the US on the 15th of May 1940 and were a resounding success.

About 192 million pairs had been produced by the time the US entered the war in December 1941, and DuPont turned over all nylon to the US War Production Board to be used for parachutes, rope, and any other essentials for the war effort. The availability of stockings for civilians became extremely limited, and women were encouraged to take good care of their stockings to make them last longer.

Many British service men felt that the US military were not only “Overfed, overpaid, oversexed, and over here”, but they seemed to be able to get their hands on bootlegged nylons, which in turn helped them to get their hands on British women... Uncle Frank probably used cigarettes to barter for nylons for his sisters.

On the subject of cigarettes, about 75% of the British troops were smokers, those who didn’t used them to trade for other goods. Uncle Frank seems to have been saving up cigarettes to take home on an upcoming leave that he was looking forward to.

It was heartwarming for me to feel the love that Frank felt for his family and which they reciprocated.

He wrote the letter on March 6, 1942. Nine days later he was killed.

|

|

|

|

A Malta Highlight 2

Gordon Findlay |

|

|

There were a couple more marching displays, then it was time for the climax of the Retreat ceremony: the playing of The Last Post by the silver buglers of the Royal Marines. After all these years, I can still bring that scene to my mind as brightly and clearly as if it had happened yesterday.

We were brought to attention, sloped arms, and stood stiffly as, up on the ramparts high above the harbour, four Royal Marine buglers in their blue uniforms with the white belts, marched stiffly along the ramparts, then halted one after the other about four paces apart, and did a quick left turn to face into the parade square.

All the other lights around the parade square were then shut off, until there were only four spotlights shining on the four Royal Marine buglers.

They slowly raised their bugles and, as one, began to play. There was no other sound. The piercing notes of The Last Post soared out from the ramparts and went echoing around the parade ground, the pure notes rising high above the rocky escarpment then fading away across the dark waters of the Grand Harbor below.

Standing there at attention, I felt that shiver which jolts the spine, makes the skin pucker as if shocked by electricity. Not a shiver of fear or fright, but one of pure cosmic pleasure, something to tell you that this special time, this feeling, this moment, is like nothing you have ever felt before. The throat tightened as the pure and liquid notes of The Last Post rose and died away in the warm night sky.

I stood there, moved with emotion, and I thought to myself: “I never want this moment to end.”

|

|

|

|

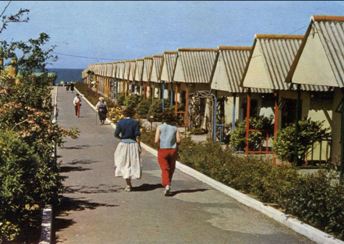

Did You Wish You Were Here?

Bill Kidd |

|

|

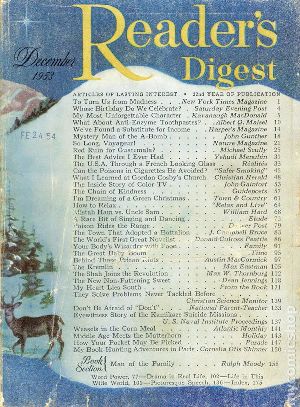

It’s on the Cards

Cigarettes were an expensive luxury item until the 1880s when the invention of the cigarette making machine industrialised what had been a highly skilled handmade item. This with aid of aggressive marketing led to a worldwide cigarette smoking boom. Mechanically made cigarettes were sold in paper cartons that were vulnerable to damage and manufacturers introduced cardboard stiffeners to counter this. By the 1890s some market savvy salesman realised that by printing information and illustrations on the hitherto blank cardboard stiffeners a desirable item could be created. Within a few years a new collectable hobby, the collecting of cigarette cards, had evolved. The marketing folks quickly realised that by releasing a numbered series of up to fifty cards on a specific theme they had found a mechanism to ensure that smokers would be faithful to their brand. Over the next half-century cigarette cards and sometimes albums to house them were issued featuring film, radio and theatre stars, sportsmen and women, aviators, politicians, flora and fauna, and just about anything else that you can think of! This bonanza of collectible trivia continued in the UK until the WW2 need to save paper put and to it in 1940 when I was barely five years old.

I can remember asking for and being given cigarette cards by my uncles and family friends. I have no idea what I did with them or where they ended up and as they never made a reappearance after WW2 ended that was the sum total of my interest in cigarette cards. However, sometime towards the end of my primary school education the local shops around the school started selling a new catchpenny product, Swap Cards. These cards were sold, five in a packet, for 3d. The cards were of a similar size to cigarette cards, and they were printed on poor quality thin card with the illustration on one side and text on the other. As I recall, there were an assortment of topics in each package. The individual cards each had the series title and number and a brief text on one side and a tinted photograph, drawing or caricature on the obverse. Their quality bore little resemblance to the cigarette cards, but they were fun to have and play with.

Once these cards became fashionable with the majority of one’s school friends the serious business of swapping to build complete sets began. Soon a market built up, clearly some cards or series were more common than others and could command a premium. Complex bargains were struck, syndicates were formed, rumours of who had some hotly pursued treasure were circulated, theft and threats were not uncommon. I can still recall the sense of elation when my purchase contained the image of a longed-for film star or international footballer. It was a different story when I found cards that I already had in my new newly purchased pack.

Even the common duplicate cards served a purpose, those that could be profitably disposed of were swapped but those that remained became the important part of gambling games. As I recall there were two such games, the most popular was known as “Same or Diff.” This involved placing a card, unseen by your opponent, either picture up down on the back of one hand and covering it with the other. Your opponent, having done the same, guesses “Same or Different,” both players remove the hand covering their card, if both cards show the picture side or text side then whoever said “Same” wins and keeps both cards. Usually this game was played fairly and without rancour, but I do recall a major losing streak playing with a much older boy who cheated by placing his card between the palms of his hands and letting me show my card first. It took me a couple of sessions to realise that he could guarantee a win by simply turning his hand. (If you are reading this, I know who you are!) The second, less popular game was a version of Pitch and Toss that involved flicking cards towards a wall, the winning card was the one closest to it. There were many variants to this game but none of them ever appealed to me.

Collecting these cards continued to be popular for a couple of years then simply faded away. Their demise was probably due to the absence of the marketing effort that was put into cigarette cards as an aid to selling a particular brand of cigarettes. The Swap Cards of my day needed a similar and probably less dangerous product to support them. No doubt the forthcoming World Cup will see further issues of Panini Stickers. Imagine what a set of Scotland players would be worth if we won!

Note

Panini is an Italian company that produces books, comics, magazines, stickers, trading cards and other items through its collectibles and publishing subsidiaries. Headquartered in Modena, it is named after the Panini brothers who founded it in 1961.

|

|

|

|

Fellowship of the Ring

Hugh McGrory |

|

|

On arrival in Canada in 1966, I joined the consulting engineering firm that had offered me the position while I was still in Scotland . Sometime during that first year I noticed that many of my colleagues wore similar rings and finally asked one of them what that was all about. This is what I learned:

In 1907 work was underway on the Quebec bridge, crossing the mighty St. Lawrence River and destined to be one of the engineering wonders of the world. It would be the largest structure of its kind and the longest bridge in the world, outstripping the famous Firth of Forth Bridge in Scotland.

Sadly, on August 27th, due to a mix of incompetence and arrogance on the part of design and construction engineers, the bridge collapsed. Seventy five of the eighty six workers were killed including thirty three

world-renowned Mohawk ironworkers (Skywalkers) from the local Kahnawake community. The tragedy was compounded when ongoing construction of the ill-starred bridge was interrupted again on 11th September 1916, when a new centre span being hoisted into position fell into the river, killing a further thirteen men.

The bridge was finally completed and still serves today (it is the longest cantilever bridge in the world), but

the tragedy of its construction damaged the reputation of the engineering profession.

In 1922, a University of Toronto civil engineering Professor, Herbert Haultain, came up with an inspiring idea. He wanted to establish an organization to bring graduating Canadian engineers together and featuring a membership ceremony to highlight their ethical commitments to the citizens they serve – somewhat akin to the Hippocratic Oath of the medical profession (‘Do no harm’).

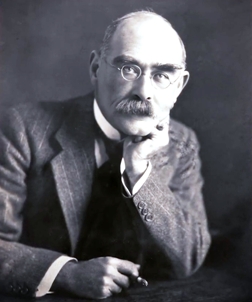

The Quebec Bridge tragedy acted as a catalyst, and the idea gained support from the Engineering Institute of Canada. Haultain contacted the Nobel Prize-winning author, Rudyard Kipling who had featured engineers in several of his works (particularly the ‘Sons of Martha’ in which he refers to all the engineers of the world, who toil ceaselessly to make sure that the world goes on functioning smoothly, letting the “Sons of Mary”, i.e. the rest of mankind, enjoy the fruits of their labour).

Kipling was interested, helped to design the ceremony, and wrote an Oath of Obligation. He said "The Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer has been instituted with the simple end of directing the young engineer towards a consciousness of his profession and its significance, and indicating to the older engineer his responsibilities in receiving, welcoming, and supporting the young engineers in their beginnings".

| |

|

On completion of the ceremony, each engineer is allowed to select a ring that fits the small finger of his/her dominant hand, either made of iron or stainless steel, and is expected to wear it every day as a reminder of their Oath.

I liked the idea but assumed I was not eligible since I didn’t graduate from a Canadian University. However I later found out that the ceremony was encouraged for all

engineers licensed to practise in Canada, attended a ceremony at the University of Toronto, and became the proud owner of an Iron Ring that I wear to this day.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

The Music and Dance of Wales, Ireland, and England.

Brian Macdonald |

|

|

A remark in an email by a Welsh family member that he was going to settle down with a cup of tea and enjoy a broadcast of the Welsh National Eisteddfod got me thinking about the musical and dance cultures of the countries that make up the British Isles. It’s always a dangerous thing to generalise but here goes.

All four of Scotland, Ireland, England, and Wales have traditional folk songs much loved and kept alive, generation by generation. And not all folk songs must be from antiquity. From time-to-time new songs are composed which take the public’s fancy and become part of the fabric. The American group of Peter, Paul and Mary was one of the early groups of the 1960s folk revival, out of which many folk songs have come, to be adopted into the catalogue along with songs from antiquity and those composed over the centuries up to the present day.

But not all the four countries have the same powerful culture of music and poetry which is high in Welsh life. The word ‘Eisteddfod’ is from two words in the Welsh language meaning ‘sitting together.’ An annual Welsh National Eisteddfod at which specially composed songs and poems are performed takes place in August. There are competitions to decide the best contributions. There will also be displays of traditional dancing, which to me looks and sounds like a looser form of Scottish Country Dancing, something I have found to be the case of the folk dancing of other English-speaking countries. The basic format of a set of four couples performing figures and movements is likely to appeal to many diverse cultures.

At the Welsh National Eisteddfod a bard’s crown is competed for over the composition of a poem which must conform to a strict compositional form. The ceremonial ‘Chairing of the Bard’ is a highlight of the Eisteddfod, and the award is prestigious. A chair is designed and constructed specifically to be ‘The Bard’s Chair’ each year. There may be no bard chosen if the judges deem the quality of the entries to be of too low a standard.

Wales also has a flourishing tradition of choral music and there are many choirs, often male voice choirs such as the world-famous Treorchy Male Voice Choir, male because 150 years ago, when the choir was founded, women did not participate in such organisations. Choral music fitted with but was not confined to the Welsh devotion to the Christian religion and hymn-singing. The Welsh harp is not just a musical instrument that may accompany a choir or with the harpist as a solo singer but is a national symbol. Wales has also produced fine tenors. The name Harry Secombe will be known to many of my generation. Secombe was not only an actor and a comedian but had a good tenor voice and made a number of records that sold well. He was also a founder-member of The Goons, who revolutionised radio comedy in the 1950s when radio was king and who inspired a generation of schoolboy imitators. Aled Jones is a current Welsh tenor of note and Bryn Terfel is a fine operatic bass-baritone.

I do not know of a comparable national music and poetry celebration native to England, Ireland, or Scotland, although Scotland does have a Gaelic music festival. We each celebrate our nationhood by voice in our own way. England has a robust history of folk songs of regional significance. Often thought to be ancient is ‘The Lass of Richmond Hill’, a rousing love ballad written in 1789, that celebrates an admired young woman of the historic hill town of Richmond in Yorkshire, not the town of the same name in Surrey, as many think. That town, largely flat, is best known for the splendid Hampton Court Palace, built by Henry VIII’s advisor Cardinal Wolsey to be his home, and later gifted, involuntarily, to Henry.

England does not have a general dancing culture. Morris Dancing, dating from the fifteenth century, is seen live and on TV but is usually performed in a town square or a street by a team of male dancers wearing white clothing and traditional bells on their shins and shoes. Sticks, swords, and handkerchiefs are common accessories. A solo musician or band, in the same costume, will accompany them.

England is strong in classical and operatic music and has produced many fine singers. A favourite of mine was Kathleen Ferrier, a rich-voiced contralto from Lancashire. Her fame as a stage, concert and recording artist was international. She died in 1953 at a young forty-one, without fulfilling her promise.

England has long been fond of opera and has several highly regarded opera companies. The Savoy Opera Company and the Doyly Carte Opera Company are two noted companies which specialise in light opera. W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan created several comic operas in the late Victorian era which continue to be enjoyed by audiences.

The former coalmining areas of England have a history of brass bands from close-knit coalmining communities and of competing with one another at festivals. The Grimethorpe Colliery Band, formed in 1917, is one of the most successful and continues long after the local coalmine was closed. It was used in a film, ‘Brassed Off’ which is based on that community’s social and economic struggles caused by the mine’s closure when coalmining virtually disappeared in England in the late twentieth century.

Ireland’s song tradition, in Gaelic and English, is thriving and lends itself to ad hoc group singing. A fond memory of mine is of wandering into an empty room in a country bar in County Cork with my wife, for a quiet drink, late one afternoon. The room slowly filled with silent people, until a fiddle-player walked in. This was what folk had been waiting for and an evening-long singsong of folk music ensued.

Many Irish folk songs are patriotic, for the three provinces, Leinster, Munster, and Connaught, that now comprise Eire suffered long under English domination, with the majority native Irish population poor and oppressed and longing for freedom from the English yoke. To many Irish the fourth province of Ulster, which forms Northern Ireland, still a part of Britain, should be part of free Eire and they believe that the struggle for freedom is not over. Ireland has a tradition of producing tenors and there is a library of sentimental songs to suit such voices. ‘Danny Boy’ and ‘When Irish Eyes Are Smiling’ are two examples of this genre. John McCormack is the best-known Irish tenor of the 20th century.

Not all folk songs are centuries old. The singer Domic Behan, of the 1960s Irish folk group, The Dubliners, wrote an Irish version of a song, originally about Newfoundland, called ‘Thank God We’re Surrounded by Water’. It became wildly popular in Ireland, and its chorus was sung with gusto at dances as an accompaniment to uninhibited dancing. It is still enjoyed as a patriotic Irish folk song.

The sea, oh the sea, is the grá geal mo chroí

Long may it roll between England and me

It's one sure guarantee that some hour we'll be free

Thank God we're surrounded by water.

(Note:The Irish phrase Grá Geal Mo Chroí is pronounced graw gee-yal mu chree. It translates to "shining love of my heart" and is a poetic expression of deep affection, similar to "my darling".)

‘Tommy Makem and the Clancy Brothers’ was an American Irish folk group of the same era which became hugely successful in Ireland and many of their songs had a patriotic flavour. ‘Johnson’s Motor Car’, written in 1921, celebrates an Irish Republican Army ambush of a doctor in Northern Ireland to steal his car for their rebel activities. ‘Kevin Barry’ is an Irish rebel ballad. It tells of the death of Kevin Barry, an Irish Republican Army member who was hanged in 1920. The Northern Irish Loyalist equivalent is ‘The Sash’ (aka The Sash My Father Wore), which is the anthem of the Royalist Orange Order and celebrated the Protestant William of Orange’s (William IV of England) winning of crucial battles in Ireland in the seventeenth century. The singing of either by its adherents in public is likely to lead to a rendition of the other by an opposing group, and an escalation.

Irish dance, with its formal, straight-backed, arms unmoving and straight down by your sides posture, is an unusual style of dance and has both solo and group forms. It is believed to have its roots in ancient Celtic dance. It still features strongly as a competitive art form at festivals, and is now mostly performed by girls.

In the 1990s, the American Irish dancer, Michael Flatley, took the world by storm, with the ‘Riverdance’ stage show that showcased Irish Dance as popular entertainment and continued with more shows till recent years when advancing age curtailed this strenuous form of dancing for him. Flatley, with his snake hips, slim physique and nimble legs, adapted Irish Dance as a spectacle with new movements and large dance troupes dancing in strict tempo. Riverdance and its successor shows live and on TV were extremely popular. Flatley's shows have played to more than sixty million people in sixty countries, have grossed more than US$1 billion and have reinvented Irish Dancing as an art form and as entertainment.

The Irish harp, also known as the Celtic harp, is a national symbol of Ireland and a significant part of its cultural heritage. With a history of a thousand years, it has enjoyed a twentieth century resurgence. It is used by the Guinness brewing company on its label and by other Irish organisations and companies and features on the Irish Coat of Arms. It is related to the Welsh harp and to similar instruments of other Celtic countries.

|

|

|

|

Caring and Sharing

Hugh McGrory |

|

|

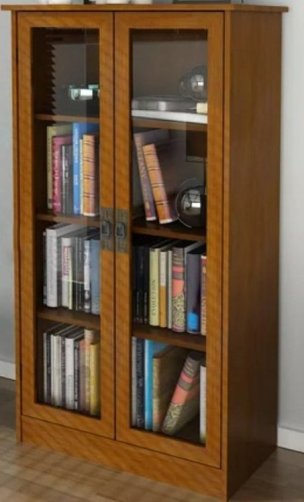

My wife, Sheila, has a part-time volunteer job at the local Care and Share Thrift Store in Stouffville. The store is run by the Mennonite Central Committee. The Mennonites are a religious community based in southwestern Ontario. Their core values are a commitment to Christianity, hard work, family and community.

On the business side, they operate a number of farms, farmers markets, a restaurant and several thrift stores. All the profits from the thrift stores are given to local and international charities, such as the local food bank, homeless shelters, support for victims of the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, etc. Last year, the store cleared over $1 million in profit. This year, they are on track to do more.

Items sold in the store include housewares, clothing, sporting goods, books, games, toys, electronics, bedding, some furnishings, hardware, tools, stationery, pictures, craft supplies, etc. The store receives donations from people in the community which are then sorted, priced and sold. Prices are very reasonable. Stock remains for no longer than one month it’s sold at a large discount to another organization to support the needy. The stock changes quickly and depends on the donations, so customers never know what they will find. Customers say that shopping in the store is like treasure-hunting.

Customers include:

- folks setting up a new home, cottage

- students looking for household goods for their dormitories

- people looking for inexpensive work clothes, party clothes

- immigrants setting up new homes in Canada

- folks looking for Christmas or birthday presents

- parents and grandparents with kids in tow looking for new toys, puzzles, educational items

- teenagers looking for sports equipment

- golfers and tennis players looking for cheap balls

- poor people, rich people, all sorts really.

The store is about 15,000 square feet in size and is staffed by seven permanent staff (the managers) and about 200 volunteers. Many of the volunteers are high school or college/university students getting work experience. Many are retirees looking for a hobby through which they can contribute to charity in the community.

There is a section of the store where high-end, unique donated items are on display in a big showcase. Items are numbered and customers register and bid on them anonymously. There are incredible deals to be had in this area.

For example:

- four high-end designer label ladies’ purses, thousands of dollars retail, for less than $100

- a set of 12 boxes of Lego for children, again retail value of thousands for less than $100

- a violin in a wooden case, over $2000 retail sold for $400

- a set of 25 Royal Doulton china dolls, thousands at retail, for $300

- collection of vinyl records by the Beatles, Rolling Stones and other great stars for $400.

You get the idea. This section is watched by customers looking for a deal. It’s not unusual to see customers monitoring the showcase and the amounts-bid sheets and then checking via their phones for the same or similar items on online bidding sites such as eBay.

Sheila says that there are a lot of people who are regulars. Some of them have told her that they love the store. It’s a nice cool place in the summer, a nice warm place in the winter, they can wander up and down the aisles at their leisure, no one bothers them, there is nice easy-listening ‘Golden Oldies’ music that everyone is familiar with playing in the background and many customers hum or sing along to it.

There are a few people who shop at this and other thrift stores for ‘deals’. It could be high-end women’s clothing or household goods. They buy the items and re-market them on other specialty websites, such as PoshMark which allows people to re-sell women’s clothing and fashion items. Sheila’s hairdresser says that one of her clients does this as a full-time business and makes a good living at it.

You never know what will sell. Sometimes the most unlikely items are gone almost immediately. A lamp in the shape of a guitar took less than 15 minutes to sell. A pair of women’s shoes with five inch heels and lots of rhinestones took 10 minutes. Staff couldn’t even get it onto the shelf because three women spotted them and stood in line to try them on. Mason jars are very popular even if the lids need to be thoroughly cleaned. On the other hand, some items seem to sit for quite a while. For example, complete dish sets, a large Waterford crystal bowl, retail several hundred dollars and priced at $40, vintage dolls, virtual reality headsets, fondue sets, coffee makers, air fryers. As mentioned, those unsold items are moved on after a month and sent to an organization that provides them to the needy.

Due to changes in the economy, thrift stores seem to be increasing in number, and they do have the extra benefit of being a sensible way to recycle products and reduce the amount of goods being send to landfills.

Some people seem to regard them as ‘junk shops’ and it’s true, there is some questionable stuff in them - but ‘one man’s junk is another man’s treasure’, and treasure-hunting has fascinated people for centuries.

|

|

|

|

More Coincidences...

Jim Howie |

|

|

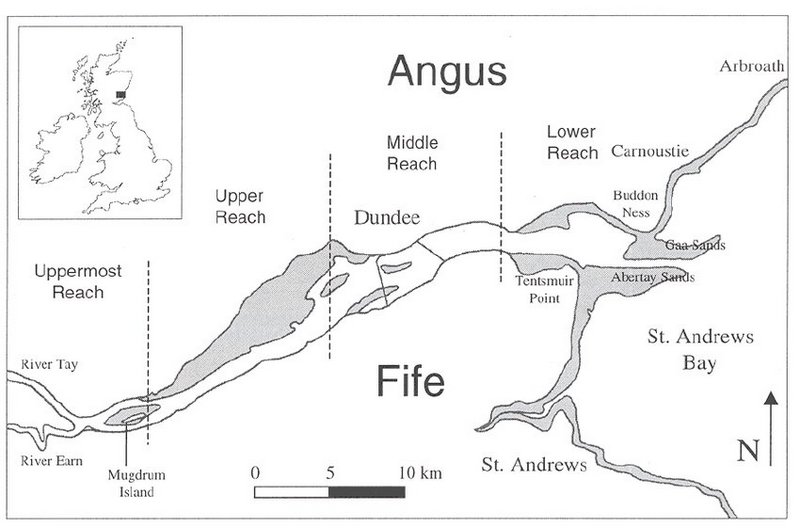

Recently, on leaving our holiday cottage in Kirkcudbright (pronounced Kir-COO-bree, about 180 miles from our home in Dundee) we stopped to admire our neighbour’s garden. As we did so a couple of similar age approached, and we got into conversation with them.

My wife asked where they were from, and “Kilmarnock” was the reply - we told them we were Dundonians and on holiday - the man said “I used to play for Dundee Football Club". I asked his name, and he said “Ian Ure”. Then came my Doctor Livingstone moment when I replied (not “Oh, I remember you playing”) but - wait for it...”You were Raymond Stern's Best Man.” He was flabbergasted…

I phoned may old schoolmate Raymond, and after a conversation, told him I had someone beside me who would like to speak to him and handed the phone to Ian. Raymond was blown away at the coincidence.

In a further coincidence Ian Ure had lived in Barnes Avenue while playing for Dundee, and I was born on that street!

You couldn't make it up… and we’re not done yet:

Five days after meeting Ian Ure I was speaking to Paul Hegarty Dundee United Football Club’s League-winning captain, and a centre half like Ure.

So, two league-winning, Scottish International centre halves within less than a week - not bad going for an octogenarian!

|

|

Any time I see a baby on TV my mind always says “Ahhh” to me - it almost always makes me smile and sometimes l even laugh out loud… I suspect you may well react the same way – probably baked into us through natural selection.

Speaking of which, have any of you ever looked at a baby and thought to yourself “Babies are so helpless and inept how does the human race manage to perpetuate itself?” Presumably the answer also lies in the natural selection processes of evolution. I decided to explore the issue:

|

"Oh for pity’s sake - what the hell is altriciality?"

|

Altriciality is the opposite of precociality, of course. Precocial species in birds and mammals are those in which the young are relatively mature and mobile from the moment of birth or hatching. Horses for example - newborn foals are neurologically mature and are capable of standing, walking, and coordinating their bodies shortly after birth - this allows them to flee danger and nurse from their mothers relatively soon after being born. Some ducks are born fully feathered and able to swim after their mother almost immediately after birth.

Altricial species are those in which the young are underdeveloped at the time of birth and require the aid of their parents to mature after birth. Humans of course, domestic cats and dogs, most rodents, and many birds like songbirds, hawks, and owls.

So how does this give humans an advantage over other species? There are a number of reasons:

Forty weeks seems to be, on average, the optimum time for human gestation. It ensures that the baby’s head doesn’t exceed the size of the mother’s pelvis. It’s also a sweet spot in the trade-off between the physical demands on the mother’s body versus the benefit for further development of the baby in the womb.

The baby’s head and brain continue to develop after birth enabling sophisticated cognition, language, and social learning at the expense of having to be supported by parents for a longer period.

Being helpless encourages infants to focus on their caregivers, leading to the development of strong social bonds and the ability to learn complex social skills, language, and culture.

When I look at the photo above, I have to think that the process of natural selection has done a pretty good job over the past millions of years.

Bet you smiled at both photos...

|

|

|

|

The Case of the Swedish Ambassador’s Daughter 2

Clive Yates |

|

|

The long over-night London sleeper train pulled into Leuchars island platform, and I was standing there looking about me to see if anyone was alighting. I noted the guard taking luggage off at the head of the train. I looked for the passenger, and after a brief delay, a young lady popped into view at the very far end of the long line of sleeper-carriages. I went to meet her as she took in the windswept fields surrounding the island platform. By the time I reached her, I heard the clatter of doors, the guard’s whistle, and immediately the train began to move away northwards. When I reached the young lass, I turned around and saw that there was now a long, deserted, platform.

The young lady became visibly distressed telling me that the guard had not off-loaded her trunk from the Guard’s van at the head of the train. Full of confidence, I asked if it had the special ‘St. Andrews’ sticker on it? Assured by her that it did, I comforted her by confidently saying that it would be taken off at Dundee, and not to worry. for I would ‘rescue’ it later that day when I went to Dundee. The Porter reassuringly told me he had re-loaded the Trunk because it did have ‘our’ special stickers on it. I took the young lady as a passenger to her Hall of Residence where she was duly made welcome. Much later that morning, I went to collect a load of luggage from Dundee bound for St Andrews and took the opportunity to search around for this specific ‘arrival’ from that morning train.

It was NOT there! Worse still, nobody at Tay Bridge station recollected it being off-loaded from this London-Aberdeen sleeper. I asked them to telephone Aberdeen and to start a search for it. Perhaps, too confidently I reasoned (not unreasonably) that the same sleeper carriages would be re-used for the next evening South-bound London sleeper. Again, no joy. Then came some unwanted and really bad news! Contrary to all my thinking that the carriages would remain coupled together, I discovered that this guard’s van had been re-used on a Cross-Country express departure that very morning from Aberdeen to Penzance. Now even worse news! This same guard’s van had already passed through Dundee and Leuchars on it’s southbound journey by the time I was informed, and had not been checked by Leuchar’s staff who had absolutely no reason to expect ‘stickered’ luggage from the North! It only had arrived on ‘local’ trains going North!

A degree of concern - actually, blind panic - began to set in at this point, especially as by 6 o’clock in the evening, I had to visit University Hall to advise an overly protective Warden that somehow, we had lost her charges ‘trunk’ containing all her belongings. I dutifully grovelled, apologised, and suggested that the young lady be assisted with whatever she needed at ‘My’ expense in the meantime.

Later that evening, I re-visited Leuchars station staff and explained what had happened and they agreed to instigate search proceedings throughout the British Rail network seeking information as to the present whereabouts, and urgent return of ‘the trunk’! I had to give all the details to them including the young ladies name, and it was at this juncture, I took the liberty of ’upping the anti’ by adding an ‘inspirational’, fabricated detail ! The young ladies real name had a Scandinavian ring to it (and for present confidentiality, I ‘encrypt’ it now as ‘Olafsdotter’!) In desperation, I gave British rail employees her proper name – adding that I had been told that she was... ‘The Swedish Ambassador’s Daughter', and all Hell was being let loose!

On the following day, about midday, we had a telephone message to the Students Union that the trunk had been located somewhere in the West Country and it was being re-routed back through London for onward travel to St Andrews. Good News and relief for me in particular. Later that same day, I was informed that the ‘trunk’ had been delivered from Edinburgh by courier delivery direct to University Hall. As far as I was concerned, “all’s well that ended well!” It was now firmly in the past. Everybody had done their job; been rewarded; enjoyed their ‘tips’, beers, and curried flavours. Now to the serious business of endless Studies and complaining about the food!

Except there was a sequel. At a Student Union reception for ‘Freshers Week’ workers - to which I was invited a few weeks later, the Master of the University, (the late Dr Kay McIver) sidled up to me during the reception and was chatting away generally about ‘other-things’ when she suddenly switched topic with an incidental... “I must thank you personally for rescuing the ‘lost trunk ...”

(I had to guess she probably had been informed about it by the Hall Warden.) Fortunately, I did not react in any way, but simply just listened to see where this was going. Warily and vaguely, I defensively muttered that I had only done what any reasonable person would have done to rectify the situation.

Suddenly, completely out of the blue, she went on to enlighten me for the first time that the British Railways Chairman’s Secretary had telephoned personally to the Principal of the University, (Prof. Stephen Watson) to offer sincere apologies for the embarrassment caused by having lost this trunk in the first place, and to advise him that they had located the missing article, couriered it to London Heathrow; sent it on the next available flight to Turnhouse Edinburgh, and that it would be delivered safely by courier to its owner in St. Andrews.

Immediately, my sixth sense warned me we had moved into completely uncharted and extremely dangerous territory! Then, fixing me with a glint in her intimidating eyes; she pounced and posed her intended question.

“I wonder where on Earth these people got hold of this ridiculous story that the ‘Trunk’ belonged to the Swedish Ambassador’s daughter?”

“Don’t ask me, Dr McIver...

Perhaps I can get you another Sherry?”

|

|

|

|

The Case of the Swedish Ambassador’s Daughter 1

Clive Yates |

|

|

I went to the University of St Andrews in 1977 at the age of 39. One would be correct to say that I was a very ‘late’ developer! Excepting by then I was commercially ‘worldly-wise’ and always quick to spot opportunities to obtain extra ‘pocket money’ when the occasion arose.

Many will know that St. Andrews no longer had its own railway station (thanks to Dr Beeching) and had to rely upon nearby Leuchars Junction, for local services, and for two daily direct trains from or to London (including the ‘Aberdonian’ Over-Night Sleeper.). British Rail did offer its passengers who advance-purchased their tickets a helpful option to forward their luggage 'in advance' to the destination station on proof of their actual ticket.

I persuaded the Students Union Council to advertise this widely to incoming ‘freshers’ (some 60-70% of our students came from the South.) I then offered and ‘contracted’ myself to collect and deliver that luggage (for an appropriate ‘fee’) from the station to Halls of Residence. We advised incoming students about this facility and provided them with instructions and a special WHITE sticker with a BLUE St Andrews Cross with their name and Hall details. These were to be affixed prominently to one end of each item (trunk, bike-saddle, cases.)

The Union expected me to pay all my own expenses from these associated pre-paid fees. This proved to be an absolute ‘El Dorado’ which supplemented my student grant enormously. Many distant ‘English domiciled’ parents positively encouraged their offspring to use rail (rather than parents travel time commitment and over-night expenses incurred in assisting them). We simply were inundated with requests –and to my delight and much more to the point, the prepaid ‘fee’ cheques!!

So far, so good ... except Leuchars Station had not sufficient storage space available. However, they did agree to re-direct trunks, bicycles and other cases forward to Dundee Tay Bridge Station which had plenty of indoor space. Problem solved! Despite the extra distance involved, it allowed me to store, sort, and optimise for my own convenience deliveries into each Hall of residence. I did not tell anyone that I had the free use of my brother’s large, 35-cwt Volkswagen van in Dundee. The sorting task kept me busy for several days at the beginning of several successive ‘Annual’ Freshers Weeks. It really was a dream operation where I was able to employ others willing to collect fees and answer queries at a help desk in the ‘Union’ in return for smokes, beers, meals, and a celebration Curry meal at completion.

All went well, successfully, and very profitably, ... ... until one Tuesday morning when I met the over-night London sleeper train at Leuchars at seven in the morning, and the Swedish Ambassador’s daughter entered the picture…

To be continued…

|

|

|

|

Telegram Boys

Hugh McGrory |

|

|

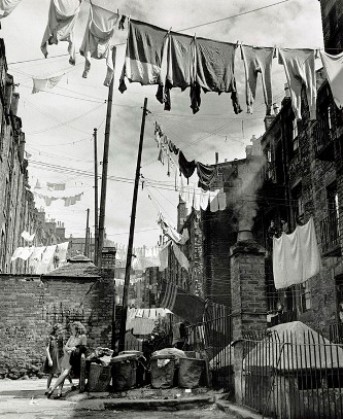

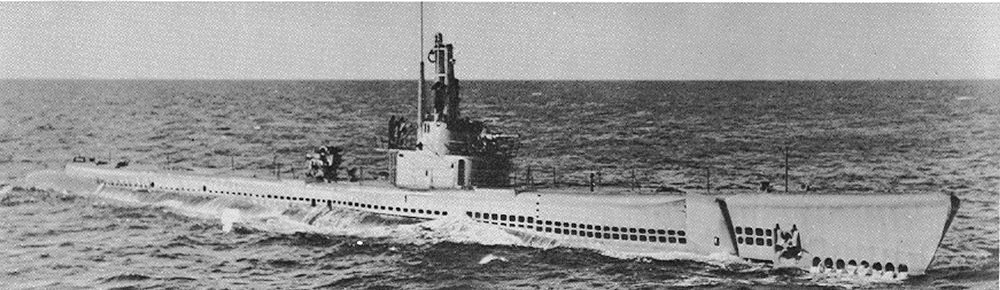

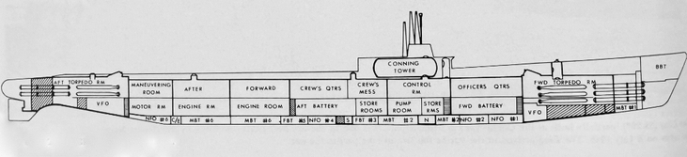

During World War 2, over a nine-month period in 1941/42, my grandparents shared the sad experience of losing a son – so my dad lost a brother, Wullie (who died at the age of 32 when his merchant ship was torpedoed mid-Atlantic), and my mum also lost a brother, Frank (who died at the age of 20 in an RAF airplane crash in Iceland).

I was four at the time, so I don’t remember anything of that traumatic period for our family, but it occurs to me that my grandparents on both sides of the family most probably received the 'dreaded telegram' such as the one below.

In the first half of the 20th century the ‘last mile’ of telegram delivery was by means of cadres of ‘Telegram Boys' who worked for the GPO (General Post Office) until the service was ended in 1982. These were boys from 14 to 17 (school-leaving age was 14, and at 18 boys could become postmen). They were paid about one pound per week and worked six eight-hour days. They were provided with two uniforms a year, one winter and one summer weight plus one pair of shoes and one pair of boots a year, plus overcoat and walking cape and a pillbox-type hat. They were also provided with one of the heavy old red bicycles used by the Post Office at the time.

| |

|

The delivery protocol was that the boy knocked on the door, gave the telegram to the addressee, then waited to see if there was a reply (if so, they wrote it down on a form then took it back to headquarters).

With the advent of war, a change had to be made. Imagine this scenario… a 14 year old kid knocks on the door, the lady of the house opens it and reads the message - basically it says, “Sorry, your husband / son has been killed in action.” What happened next would have ranged over a spectrum of reactions, not one of them likely to be well-handled by the poor young messenger boy.

A change was made so that ‘death/ injury/ missing’ telegrams were identified so that when faced with such a delivery the telegram boy would simply hand it over then depart immediately.

A telephone boy relating, in his old age, his experiences said, “I can remember delivering one such telegram to a 3rd floor flat and, having handed it to the lady turned to go back to the lift and whilst waiting for it to come I could hear screams and smashing crockery coming from the flat I had just left.”

Another said “I can still remember vividly a lady who on seeing me at the door when she opened it, took the telegram, danced a little jig in front of me, and called to someone at the rear of the house "Oh, its a telegram from Bill, - he's coming home on leave and has sent a telegram to say what train he will be on" . Alas it was not to be, it was a message from the War Office to tell her that he had been killed in action. On reading the message, the poor girl collapsed in front of me and sobbed her heart out. I was then only 14 or 15 years old, and I hadn't witnessed an adult react quite like this before. I felt so helpless and didn't know what to do."

People were very sensitized to the sight of a telegram boy appearing on the street, hoping it wasn’t for them, and when it wasn’t, there would be an army of womenfolk descending on the bereaved house and they would take over the practical side of things, like taking the children away, making tea, and generally just being there.

Almost ten years after losing her youngest child, Frank my (by then widowed) gran on my mother's side received the letter below from the British Legation in Reykjavik:

|

|

|

|

A Malta Highlight 1

Gordon Findlay |

|

|

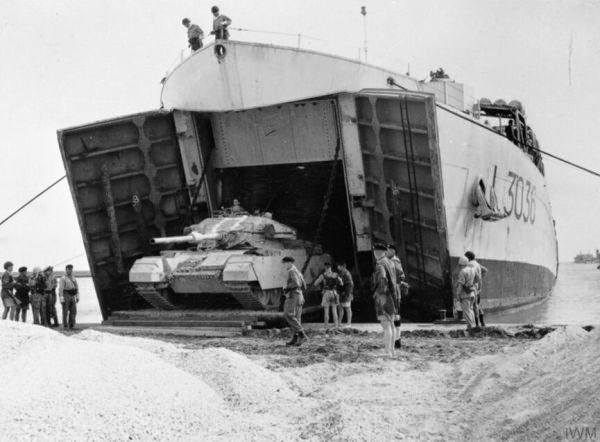

One of the highlights of my time in Malta was the Retreat ceremony. This was a once-a-year event staged on the parade ground overlooking the grand harbor of Valetta – one of the truly great views on the island. Essentially it was “showing the flag”, a chance for the British and allied troops on Malta to put on a show for the islanders.

The big day itself, of course, was preceded by a full day of preparation: washing, cleaning and blanco-ing of belts and webbing, polishing brassware, brogues and boots, pressing kilts, brushing bonnets, cleaning and shining up rifles. Everyone was involved. Even we nerds in Intelligence would be marching with the rest of 1st Highland Light Infantry in best battledress tunics, kilts and sporrans, checked hose, white gaiters and brogues.

The parade began around 4.00 o‘clock in our barracks at Aijn Tuffeiah with an inspection by our own C.O. Then we piled into 3-ton trucks and were driven to the outskirts of Valletta, where we formed up behind our own pipe band (a very good one) and a military band from the Royal Marines.

I think there was also a regiment of the Kings Own Scottish Borderers on hand, since they were in Malta at the same time as we were.

Around 6.00 p.m. the sun was still bright but beginning to come down, when the ceremonial march through the city began. The bands struck up the first notes, we came to attention, sloped arms, our R.S.M. screamed out “Quick March!” and to the strains of “Scotland the Brave” our columns moved off, thumping in unison down the rough stone streets of Valetta.

I have to be honest: there’s no feeling quite like it: in your best outfit, your kilt swinging above your knees, shoulder-to-shoulder with your mates, rifle on your

shoulder, eyes fixed straight ahead, chin up, hearing the steady beat of the kettle drums and the wailing of the pipes backed up by the thumping notes of the military band, marching past the throngs of Maltese lining the streets, waving and clapping and cheering . . . Man oh man! You feel ten feet tall.

We marched down to the big parade square which was ringed with elevated seats for spectators plus a grandstand for the VIPs just as the shadows lengthened and darkness fell over the island. One by one the various units came crashing to a halt, we ordered arms, and the Retreat ceremony began.

It featured the massed bands playing some famous marching songs like “Colonel Bogey”; there was a bit of countermarching from a couple of drill squads, and a display of drumming from our own pipe band.

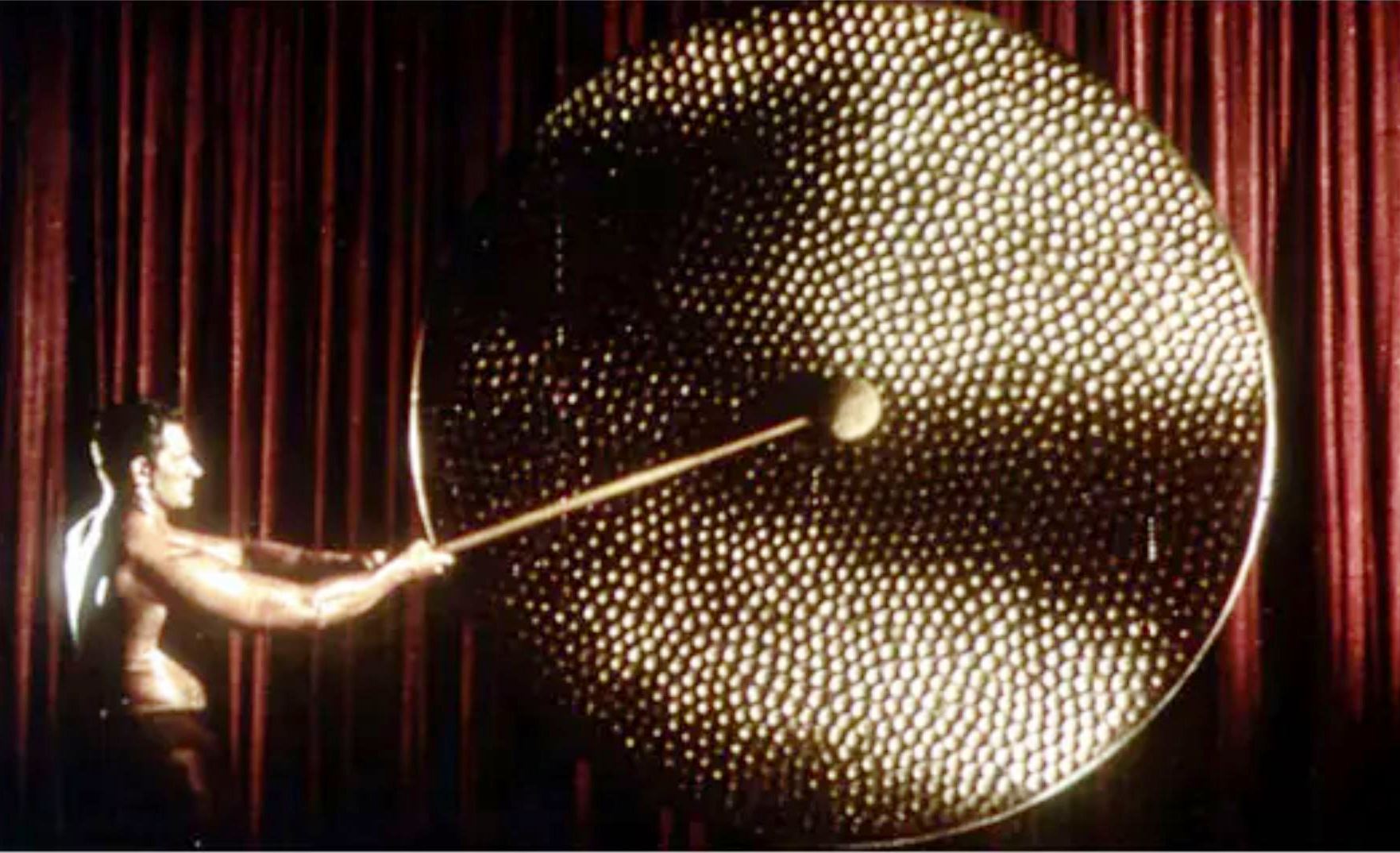

|

Massed bands on Parade Ground in Valetta back in the day.

|

I recall there was also an inspection by the Maltese prime minister, the local Governor, and a visiting dignitary from Britain, plus the mayor of Valetta. By then it was dark and the spotlights around the square came on.

To be continued...

|

|

|

|

Testing ...Testing...

Hugh McGrory |

|

|

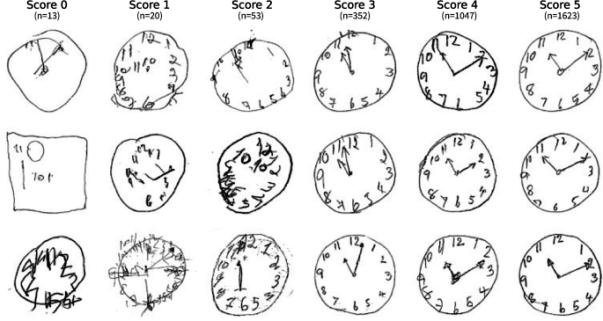

Spending so much time on these stories over the last ten years has resulted in a lot of introspection on my part. One of the things I’ve recognised is that I like being tested. I like measuring myself against various norms to see how I do…

Maybe this was something I grew into, since I remember, in early primary school, each of us being asked by the teacher to stand up and do some very simple mental arithmetic – and hating it. I don’t know if I just wasn’t very good at it, or perhaps, because of my shyness, I didn’t like being in the spotlight. However, by the time the 11+ came along I seem to have adapted to sitting tests/exams and quite enjoyed the experience.

( The 11+ examination tested a student's ability to solve problems using verbal and nonverbal reasoning in mathematics and English. The intention was that the eleven-plus should be a general test for intelligence (cognitive ability) similar to an IQ test. Students were then streamed to an academy, for five or six years, or to a secondary school, for three years.)

I remember we were also told that we were going to take part in a comparison of the English and Scottish systems by sitting the English version of the 11+. We duly sat this exam, which I quite enjoyed, - we never did hear how they compared…

When I was about twelve the Dundee Police began offering the Cycling Proficiency Test. I tried to get some of my classmates, or my street buddies interested to no avail, so I went on my own, one Saturday morning, to St. Michael’s Secondary School in Grahame St. The school playground was laid out with tape as a small

|

The school playground as it was then. St. Michael's closed in 1975.

|

street circuit. A big, intimidating, policeman was in charge, and we were asked to do various manoeuvres, stopping and starting, left and right turns, in and out of pylons etc. For everything we did we had to use the proper hand-signals. I’m told there was also a written test, but I don’t remember that. After a final critique I cycled home to show my parents my certificate…

In retrospect, I think the test was good conceptually, but I don’t think it did much, in the long run, to change the way I rode.

I’ve talked about the wall across the street from my home and how I challenged it ‘because it was there’. If you’re interested the story's here.

When I was working in the engineering department in Glenrothes. Fife, we used to get together each morning for a ten minute coffee break in the drawing office. Someone drew our attention to an advert for Mensa in a magazine. It offered a small test which you could try, then send it to them. If you did well, you’d be allowed to sit the official membership test. (Mensa is an international organization for individuals who score in the top 2% of the general population on standardized intelligence tests. It was founded in 1946 in England with the goal of providing a stimulating intellectual and social environment for its members. The name "Mensa" is Latin for "table," symbolizing a round-table society where all members are considered equal regardless of background.)

As a lark, we copied the test and about ten of us each completed it and sent it in. A week or so later most of us were invited to come to Edinburgh to sit the supervised test. I said, “Lets go guys.” I got no interest – nobody wanted to try.

The trip was about an hour by car and the small fee covered the test and the first year’s membership. So I signed up and went and sat the entry test on my own. (Re. the result, in simple terms, if you passed, then met with 99 random people, then one would be ‘smarter’ than you, and 98 would not.) Some cynics say that all the test really tells about you is how good you are at doing such tests…

So do I now have a seat at the table? Well, actually, no. They invited me, but I didn’t accept the offer.

Interestingly, some dozen years later, I sat the SAT exam for admission to the MBA program at the University of Toronto and got almost exactly the same result.

I’ve mentioned in the past that I played squash twice a week for about thirty years ending when I was 69. I loved testing myself against my opponent in a mano a mano competition – elation when you won and no excuses when you lost...

Finally, it’s good to remember that so-called ‘smart’ people can still do stupid things:

In the nature (DNA, genetics) v nurture (environment) controversy regarding what shapes our traits and characteristics I believe it’s about 50/50. Regardless, and no credit to us, my brother and I together with our two double cousins seemed to strike it lucky. We seem to have come from two lines of ‘good’ DNA and were brought up in loving, supportive families. We four became two Chartered Accountants, a Doctor and a Professional Engineer.

Which brings me back to ‘stupid’ and a lesson learned the hard way:

In my civil engineering studies at university, first year was not too heavy, so I didn’t need to do a lot of prep for exams. ( I suspect that I put this down to me being smart, forgetting perhaps, that much of the stuff we studied had been covered in our sixth year at school.)

Second year was different! The final consisted of exams in nine different subjects. I, of course didn’t need to spend much time studying for the finals – this gave me time for the important things in my life, field hockey, motor bikes and girl friends. Wen the results were posted I found that I’d failed three of the nine...

So did this mean I had to spend my summer prepping for three “re-sits’? Actually no, it was worse than that – the nine bloody courses were ‘grouped’ – I think there was one group of three, two sets of two, and two singles, The way it worked, if you failed one course in a group you had to re-sit the others in the same group. So I had to re-sit six exams (three of which I'd already passed)– and this was when I was working as a meat porter in a slaughterhouse during the day…

As someone said recently, “remember that so-called ‘smart’ people can still do stupid things.”

|

|

|

|

Let There Be Light

Bill Kidd |

|

|

It was shortly before my twelfth birthday that we moved into a tenement flat that had an electricity supply, until then our home had been lit by gas supplied from a meter that had, according to my parents, a voracious appetite for pennies. At that time gas lighting was not unusual in Dundee’s older tenements and wartime restrictions meant that the gradual electrification of the housing stock was put on hold until nearly the end of the 1940s. It wasn’t just wartime shortages that slowed the installation of a domestic electricity supply. The owners of many of the tenement properties were reluctant to pay for the work needed to allow their tenants to access the supply by having their flat wired for electricity. Money was scarce and as the cost of installing an electricity supply to an individual flat usually had to be met by the tenant it is hardly surprising that progress was slow.

The 1950s saw the increasing availability of desirable domestic electrical items such as refrigerators, washing boilers, vacuum cleaners, kettles, hair driers and curling tongs etc. All of them requiring an electrical supply. The cost of installing electricity in older properties was around 30 shillings a point. A point being a connection for a light fitting or (usually) a two-pin socket. This was such good business for many small electrical companies that it was only the older tenements that were in poor repair that were left to rely on gaslight. The advent of natural gas in the early 1960s saw the end of coal gas as a source of domestic lighting.

Coal gas was first produced as a very toxic by-product in the production of coke for use in metal smelting. By the end of the 18th Century coke became the by-product and the gas was being piped into factories and homes to provide a reliable light source. Initially the light was provided from a flame contained within a glass bowl and directed upwards. The amount of light given off could be controlled by the amount of air allowed to mix with the gas. At its best a gas light produced little more illumination than a candle, but it had the advantage that it could be used continuously with little need for attention.

The amount of light given off was greatly enhanced by the use of the gas mantle which had been developed

|

in the first quarter of the 19th Century. In order to use a mantle, the flame was directed downwards shining the light where it was most needed. Mantles consisted of a small, flat fabric mesh bag which was impregnated with a metal salt. At this stage it wasn't fragile. This changed when first fitted to a gas burner by means of ceramic ring, The bag was carefully lit by a taper, it inflated, the fabric was burnt away and the salt oxidised into a very delicate rigid structure, the same shape but somewhat smaller than the inflated bag. After first use, mantles were so delicate that the slightest knock made them disintegrate. Damaged mantles were common and made the light flicker and produce creepy shadows until a new mantle was fitted. To help protect mantles and to spread their light there was always a glass cover of some sort screwed round them. The

| |

|

glass cover would often be decorative with some of the grander establishments having elaborate gaslight fittings and covers.

For much of the remainder of the 19th Century in cities and large towns gas was the fuel of choice for lighting. local gas companies were formed and underground pipes to factories and homes were installed. In Dundee around 1830 a gas works was built on a site at East Dock Street next to Peep o’ Day Lane. In the 1840s a rival company was set up on an adjoining site. Both companies continued to supply gas to the city until 1868 when they were taken over by the Dundee Gas Commissioners. Dundee’s gas supply continued to come from the same site until the national conversion to natural gas in the early 1960s. The site was demolished in 1963 and has now been earmarked for the location of the Dundee Eden Project.

From childhood I have been an avid reader. I cannot remember a time that I have not had a book on the go. Life for keen readers is much easier now. In the gaslight days, when I wanted to read in bed, I had to smuggle a torch to bed with me. When we first moved into the flat with electricity I thought it was wonderful, but as there was no socket in the bedroom, I had to rely on my faithful torch again. Over the years I have acquired more sophisticated means for my bedtime reading. I have a bedside lamp that I only have to tap for it to come on or go off. I even have a Kindle electronic book that has its own light source. But would you believe this? I sometimes feel nostalgic for the soft yellowish lighting and the friendly hiss of the gas light that I enjoyed all those years ago!

|

|

My wife, Sheila, has a part-time job as a Lunch Assistant at a local elementary school. She works from 11:30 – 1:30, Monday to Friday, looking after 40 junior and senior kindergartners, ages 4 – 6 years, to allow the teachers to have a lunch break. The kids call her Miss Sheila.

Most days when she comes home, she has some charming stories about the kids – here is a selection – the children’s names have been changed to protect the innocents:

Dora, a 5 year-old, is a drama queen. If she falls or gets hit accidentally or just feels that she has been overlooked in any way, she immediately starts crying very loudly. Staff at the school have learned to just ignore her while she screams and cries, as she is just looking for attention. They let her cry and pout – she soon realises that she’s not generating any interest and gives up.

One day, Dora announced that she was going to marry Ian. Ian is a 5 year-old hell-raiser. He likes to yell out bad words, hit people, kick people, stomp around, make demands, and when challenged, protests that he has done nothing wrong.

Ian said that he had two wives: Olivia was his first wife and Ivey was his second. He also said that he had 17 girlfriends. It is true that some of the girls from the higher grades would come up to the fence of the kindergarten recess pen so that they could say hello to Ian – I guess some girls just can’t resist a bad boy...

Of these ‘older women’ at the fence, Orla, a pretty 11 year-old was his favourite. Staff found this amusing but also annoying, as he got so much attention while they were focussed, of course, on trying to correct his bad behaviour.

Ian was not a fan of Dora, so, he told her he was not going to marry her. Dora decided she would marry Ivor instead. This was a switch because, while Ian was a hell-raiser, he was also good-looking while Ivor was an awkward 5 year-old redhead with a nose that was always running with green snot. Staff were always handing him a tissue and telling him to blow hard.

The teacher asked Dora why she wanted to get married. Dora’s answer was “Well, I don’t want to be without a man,” and undaunted, she continued to pursue Ian. She would go up to him in gym class and take his hand or try to sit beside him at Storytime. Ian continued to yell in her face and push her away. Dora would then start to cry loudly, protest that Ian was being mean to her. Staff would try to calm the situation. Dora would then pout in a corner and Ian would stomp around stating that he had done nothing wrong.

The school had an agreement with several local restaurants to deliver meals to the children daily. Monday was sub day, Tuesday was pasta, Wednesday was burritos, Thursday was burgers and Friday was pizza. Parents had to order online for their child. Dora got into a mood one day and began to cry because she never got delivery as other kids did. Staff suggested that she speak to her mother and see what she said. Dora replied, “My dad is the boss in our house. I’ll speak to him after he plays soccer. He likes soccer so he will be in a good mood.” I guess it doesn’t take very long for the female of our species to figure out how to handle the male…

Billy is a 6 year-old who loves cars – and wearing shorts. Everyday when Sheila comes in, he runs up to her and says with a big smile “Miss Sheila, I have shorts on today.” He often has a new toy car in his backpack which he wants to show her. His current favourite is a monster truck which he calls a graveyard truck. When asked why he calls it that, he said that it was because there was lots of room for stuff. Billy also likes to eat carrots. His mother always puts slivered carrots in his lunch. He calls himself ‘The Carrot Man.’

Billy is also a negotiator. For example, one day at recess, he wanted to make a fort with some of the other children. They started pulling together some small chairs and stretching blankets over them. Then Billy decided to get some yoga mats for the floor and roof. The children are supposed to ask for permission before they start to pull out yoga materials, but Billy hadn’t bothered. Sheila challenged him and he said sorry, but could they please use the four mats they already had out – Sheila said they could use those but no more. Billy’s reply was “But we really need 6. Just 2 more.” Sheila said strongly that no, they had enough. Billy responded “OK, just one more.” Sheila said, “Billy, this is not a negotiation, you have enough.” Billy finally gave in.

Irene, a 4 year-old, is quite precocious. Her mother is a French teacher, so she speaks some French and will say “Comment ça va?” frequently. Irene is very particular about her lunches. She likes turkey and cheese sandwiches on rye with mustard on one side of the bread and ranch dressing on the other side. She also likes Greek yogurt with berries, white bagels with herb and garlic cream cheese (must be herb and garlic), quesadillas with cheddar cheese (must be cheddar), and blueberry fruit strips (must be blueberry so that her tongue will turn blue). One day, as she was chomping on her turkey sandwich, Sheila said “Irene, we should call you the Queen of Turkey.” Irene liked the idea and started to giggle. Dora’s nose was a bit out of joint, since she was not the centre of attention, so she inserted herself into the conversation saying, “Can I be the Queen of Jello,” as Jello is her favourite dessert (but not grape – she does not like grape…).

Irene does not eat cookies because they have sugar which Irene says is bad for you. Irene pointed this out to Dora one day as she was licking the sugary icing off some Oreo cookies before she ate anything else in her lunch box. Dora said she didn’t care and continued to lick the icing.

Four-year-old Irene came in one day quite concerned about her water bottle. It was not full, and it needed to be filled right away. She said, “I need to remain hydrated...” Irene also decided to lead the ‘cool down’ at the end of gym class one day. She started doing some stretches (yoga-style) while the teacher was stowing away the gym equipment. The other children started to follow her until the whole class was doing it – the teacher was impressed with her initiative and asked the children to clap if they liked it. They did, so the teacher asked them who would like to lead the class next time. Of course, Dora’s hand shot up immediately.

I find Sheila’s stories quite entertaining to the extent that I’ve got into the habit of asking her, when she arrives home, “Any stories today? “

|

|

|

|

A Lifetime of Motorcycling

in Retrospect

Brian Macdonald |

|

|

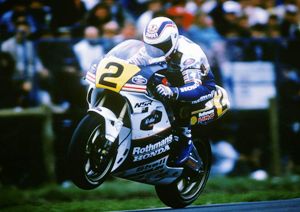

I began this series of articles with my start to motorcycle-riding at age 16 as a beardless youth who just wanted to ‘ride a motorbike’. Now, ticking off the months till my 87th milestone, I am a retired motorbike-rider with a lifetime of riding a motorbike to remember. The time comes when every individual must admit to him- or herself that a point has been reached, when, for either physical or mental reasons, major life changes must be accepted. Just before I hit 85, I knew it was time to give up motorcycle riding. I still felt well capable of doing all I needed to in order to be a safe, competent rider of a moving motorbike in traffic. But modern motorcycles with large capacity engines are so loaded with features and so elaborately designed that they are very heavy. Most BMW motorcycles weigh in excess of 250 kg. That is a lot to manhandle when the motor is stationery or at very low speed or when manoeuvring in a parking area by leg-power. It is easy to lose control. You know you have lost the fight when your machine falls sideways and reaches an angle from which there is no recovery, and the only course open is to lower it to the ground as gently as possible to minimise damage. Then the rider may have to ask for help to return the poor beast to its vertical position. Time to call it quits!

After a year and a half of being a ‘once was’ a biker, and having accepted this reduced status, I can look back on those nearly seventy years and treasure what I have got out of that lifetime of being part of a particular group of people. For, in my case, motorcycling became a way of life that brought me many benefits, much enjoyment and a few painful experiences. I have a lifetime of memories of being part of a community.